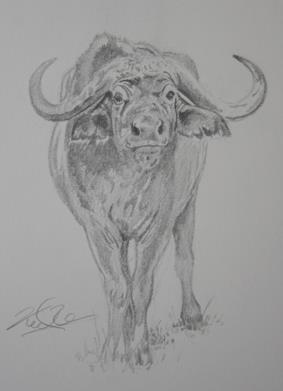

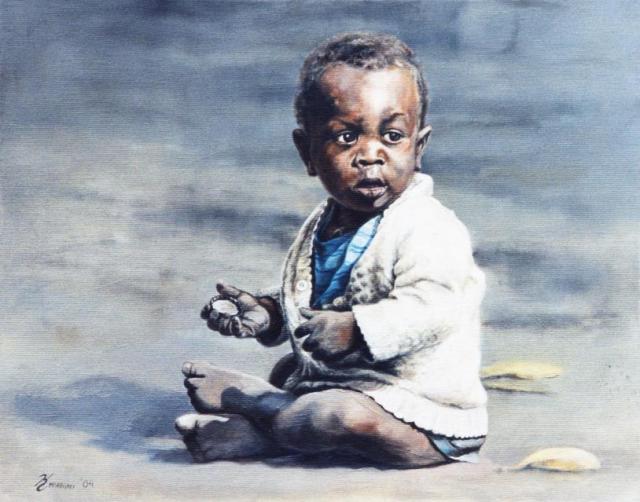

‘The Borders of Eden’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister

Somewhere deep in the forest worn rocks are hooded by swirling waters. The river makes no noise because no one is there to hear it. Usually it only appears as a hairline fracture on a satellite image.

The Ituri Forests are a green velvet mass to fly over. The waterways cut their way awkwardly to the west and the vegetation grows thickly where it is not disturbed by water, volcanic activity, or dirt tracks. It mostly just rolls and rolls.

To survive in it however is to be buried in its depth. The forest encroaches on everything, it comes as close as it can, and will reclaim the soil if given half a chance. In little places where there might be a spattering of mud huts palm trees bridle pathways as a buffer zone to the forests. Often these small hamlets open up towards a river’s edge. Dugout canoes are beached in backwaters and some elders sit under an isolated tree, which was planted years before. The men of the village sit on solid backed chairs made from a single bit of wood interlocked with a smaller piece for the seat. The women sweep and cook and fetch and clean, and the children avoid any responsibility while they can. These are the communities of Bantu people, those who came from the west; these are the men and women of the river.

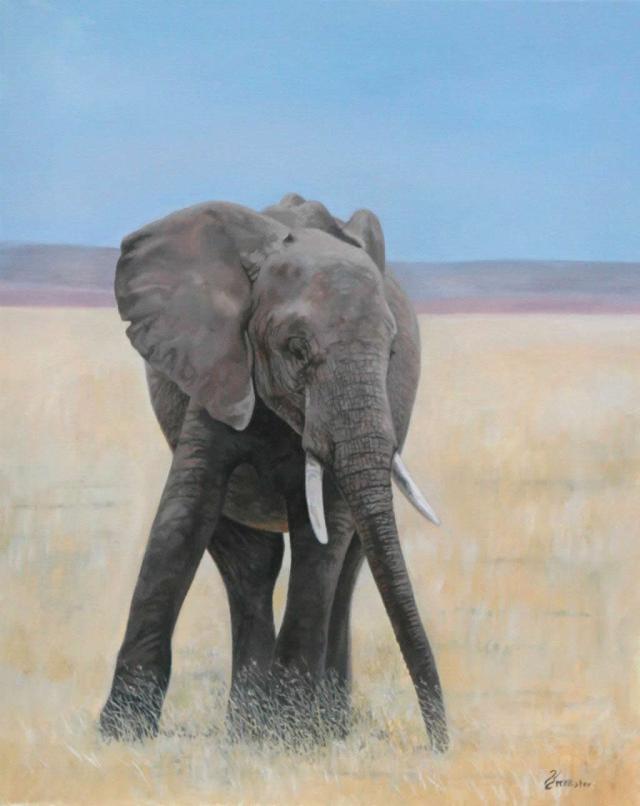

There is, however, another people, a people of the forest. Where the shadows hide a secluded world there may be little leaf covered hovels made of bent and bound branches from the surrounding forest. In the middle of the circle of these little flimsy huts hunters may dance and re-enact the killing of an elephant. They show to us, their audience, how the spear was driven and the animal bled out upon the forest floor. It is the celebration dance which marks times of abundance and feasting.

In the daily life of the family however women fan charcoal fuelled cook stoves or open fires. Men gather from the forests duikers, monkeys, honey or any number of other food stuffs. Children fetch and carry.

It is from these forested lands across Africa that I take great inspiration. Many times I flew in single engine aircraft from a forest clearing out across Lake Albert and the Semliki Valley, every time marvelling at the expanse of the Western Rift. From there the journey crosses the highlands of Uganda and western Kenya, before the land falls away again in the Eastern Rift of the same Great Rift Valley. The Western and Eastern Rifts individually represent for me very different chapters in my childhood.

My boyhood years where shaped by long journeys and short residences in villages across eastern Congo. It was a test of resourcefulness on everyone’s part. On the road the world I knew was reduced to a car seat and bag of toys, paper and pencils. The forest was thick against the roadsides and left little in the way of scenery, just endless forest. When we stopped for lunch white butterflies would come out and dance on the thick damp air.

It was not always forests for me however. The last few years we spent in Bunia, North East Congo. Here there is a land almost unique. It is a land of highland pastures covered in course grass and volcanic rock, which then dips in the east towards Uganda. This was a more open country with room to run and play.

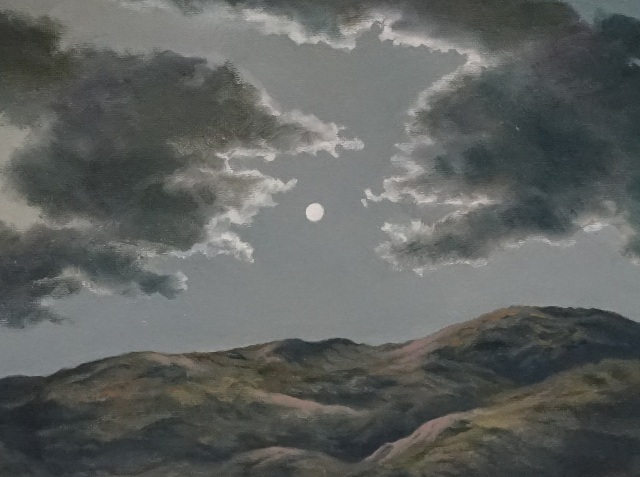

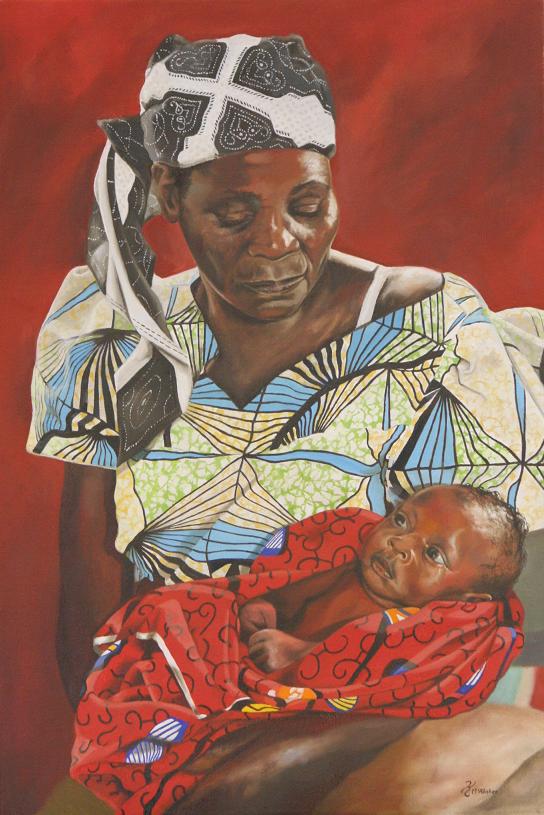

‘Wintery Days’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister

In the late 1980s we left the Congo for the picture postcard landscapes of Kenya and I subsequently discovered a new backdrop for my paintings. In different locations over the years, from mud huts to luxury hotels, I have explored and enjoyed this marvellous world of wildlife and wilderness.

Though we were based in Nairobi my family made a point of seeing much of the rest of Kenya, from Mombasa to Kisumu, and from Corr to Amboseli. I spent eight more years in Kenya before the long journey to England. It was long only because of the uneasy transition.

I went back though.

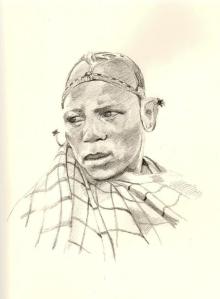

In my twenties I lived with the Nilotic tribe known as the Samburu of northern Kenya for many months. With them I trekked across deserts and the forests atop of the highest mountains in the area. Mount Nyeru provided me with ideas of leopards in damp trees and bushbuck breaking into the undergrowth like hurried porpoises as they ran startled.

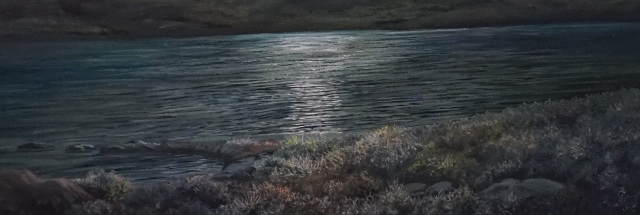

‘In The Silent Places’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister

Later still I moved through Ethiopia and saw yet more highland forests along my way. Scenes were matched with those of Kenya, and I was compelled this time to embrace the idea of painting a leopard high up on a moss covered branch where he might sit surveying the patchwork of forest leaves. I painted Abyssinian Shadows when I returned to my studio back in England surrounded by my sketches and photographs. I was driven by ambition. I rolled out six foot of primed canvas and stretched it like a drum skin until it filled the room like some great projection screen awaiting an image. After I formed the composition I stood back and saw what this painting might look like. I knew then I was about to embark on several weeks, if not months, of work.

‘Abyssinian Shadows’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister

The first thing to do was to get familiar, very quickly, with a variation of greens and blues which I had never used in oil paint before, but had seen so many times. It was an entirely new pallet from my usual one. This pallet was not chosen to emulate the dust, the heat, the sun scorched earth and grass, and the fur and hide of tired animals. It was instead to be used to illustrate the lush highland forests and deeply set colours. This painting needed to become an image of coolness, of backlighting, and of subtlety. Using these rich shades from every imaginable green needed to be tempered by orange and purple embellishments where the feeling of sunlight would dictate. I was creating a world from linseed oils, pigments, and canvas, but it needed to resemble something believable. There was an order to the highlight and shadows, as the imagined light came streaming across the canvas, but it would have to be made finally unruly by the interference from reflecting leaves and absorbing shadows.

There is barely any easy way to create depth to these kinds of paintings. The sense of a recession with the landscape here is subtle; there is no great skyline or horizon to fall back on. It is engaging on every level and with every brushstroke, because it has to remain forefront in the viewer’s eye. While addressing this reality I also had to acknowledge the need for the finished painting to be restful and without agitation.

This was in great contrast with my other paintings such as The Rarest Guest, where again I called upon the knowledge I gained from my later years in Kenya.

‘The Rarest Guest’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister

I saw a great number of new animals when we moved to Kenya. It was remarkable to see the biodiversity here in the eastern brush lands and open savannahs. But often my father would describe to me how much more game he could remember in Kenya when he was a young man growing up there (he too spent his younger years in Zaire, then the Belgian Congo, and moved to Kenya to school at The Rift Valley Academy).

On one of our family excursions, I remember seeing the most unusual hartebeest one day. It was crossing the road near Tsavo, when we were on our way back from the coast. Baffled, I could not figure out what I was looking at until many years later I saw another one in a photograph accompanying an article written about antelope conservation. I knew only then that I had seen a Hirola, or Hunter’s Hartebeest. To my horror I discovered too that this was an animal heading for extinction and I remembered my father’s warning about the destruction of the African game fields.

Sometimes I have an overwhelming feeling of despair when I think that perhaps some of the animals in my paintings might not exist in the coming years, through poaching and habitat loss. It is at times like these that the feeling of responsibility, which lies with those fortunate to have seen these animals for themselves, comes into play.

On one of my journeys through Africa I stood where two great rivers converged. Not far from Khartoum the Blue Nile and White Nile meet, and when you think of the distance these rivers have run from the heartlands of central and eastern Africa you realise the scale of things. How can the game fields be protected along this river which runs through so many countries onwards to the Nile Delta?

The bush-meat trade along the Congo River is an example of indiscriminate hunting of animals left unprotected by conservation.

But my work is rarely gloomy despite these concerns. I celebrate what does remain and what I have seen for myself. The Residence of Silence may well be of an animal heavily poached in the areas it is found but the work concentrates on the serenity which can often be found in these remote areas of Africa. The Sitatunga in the painting is statuesque in its calmness and the Bottlebrush Bird perches unmoving in the dim light. These are scenes to be celebrated and cherished.

‘The Residence of Silence’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister

Because I finally have spent a longer time in Kenya than Congo I am far more familiar with the open plains of the Eastern Rift. Where the land runs flat between ancient volcanoes and gorges, and where the grasses hide the great herds of animals, are some places I know very well. It is a constant ambition to carry on learning from these places as time goes by.

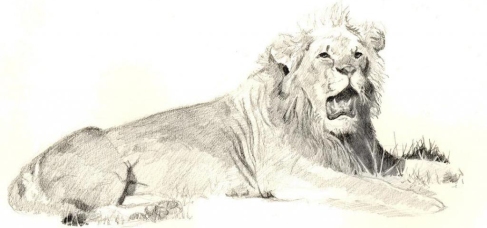

Knowing the behaviour of animals and the variety of the habitats they live in opens up a number of possibilities. In the battle for accuracy I feel more confident once these observations have been made. It is when parameters are set that the room for improvisation and interpretation has also been identified. Knowing the seasons, and the conditions and behaviour of the animals within these seasons, is a good place to start. Identifying the family bonds and relationships between more sociable creatures like the African elephant, lion or hunting dogs is another.

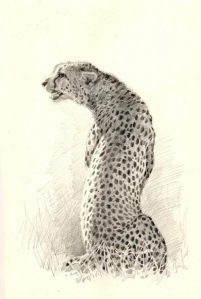

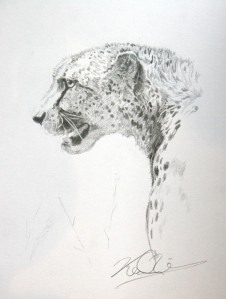

I painted The Threat of Evening after watching a young female cheetah take refuge in thick grass. Knowing that she was relinquishing her dominion, as the sun was setting, to the creatures of the night brought an image of vulnerability to an animal regarded as being amongst the more formidable. Though cheetahs remain a top predator by day they retreat to the awakening lions and leopards, and they fear the gawky bullish hyenas. This young cheetah watched for the tell tale signs of danger and slumped deeper against the ground, turning purple and gold in the embers of the sun, and it was this that stood out from the days of observation and study. The fleeting moment, the sense of occasion, and the perception of worry brought the portrait of an animal to life; it made an effort to personify, and aimed to invoke sympathy.

‘The Threat of Evening’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister

It is this concept of illustrating occasion in the natural world which comes as a direct result of a desire to capture what are unfortunately diminishing environments. The very real need for the conservation of these wildernesses across Africa is an issue ever pressed upon those who have had the pleasure of enjoying the African bush while understanding the responsibility which comes from their own sense of renewal. Some of these images may be amongst our last records if we lose the conservation battle.

There is of course the retrospective or even the romanticised and idealised sense of occasion as well. With the connotations the word safari already has attached to it there is implied an imagery of expedition, adventure and romance unique to the lore of Africa. Most of these can be a cliché but if rendered with care a painting relying on preconception can flatter the nostalgic notions and evolve into quite a tangible alteration of imagery that can be instantly engaging.

I have tried several times to address this internationally familiar notion of the Africa-of-old. Period pieces in point of fact have become an increasing percentage of my occupation.

The Man Eaters was my favourite of these attempts. Inspired by the many great tales of man versus beast on the open savannah I wanted to create a painting which relayed the feeling of more than just observing Africa but in actually engaging with it; of surviving it.

‘The Man Eaters’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister

Painting Africa is an ongoing interaction between artists and their subject matters.

When contextualising my work in comparison to my peers, friends, competitors, mentors and heroes (in no particular order) I feel the need to find my own signature and technique. Though my love is Africa and its people and wildlife I understand the need for individuality in my rendering of the scenes I have composed. There may be a gravitas in the subject matter, especially when concentrating on endangered species and habitats, but the visual language needs to be from a carefully selected set of techniques.

It is as much about selecting your mentors, artists you aspire to, and those you are willing to take criticism from. I have had the great fortune of having been mentored by the internationally acclaimed aviation and landscape artist Gerald Coulson, and later by his son Lawrence Coulson, another landscape artist. Now that my career is growing steadily we three are more likely to be seen on stools around a low table at Gerald’s local pub than in the old formal studio critique. We talk through every aspect of our work, from painting technique to business acumen, but abstractly and away from the easels.

It is paramount in any artist’s career to know where he or she fits into the market place and whose work can be regarded as being that of a competitor. This is an evolving context and you as an artist must evolve with it.

As I have recently set up my new studio in Victoria, London, I am locked away from the world but remain informed both about the animals and habitats I am painting and the market place into which my final work will be placed.

In the end my artwork, for me, is fundamentally a tribute to a land and place I love so dearly. My conservation efforts are needed I know, but I still adore what remains.

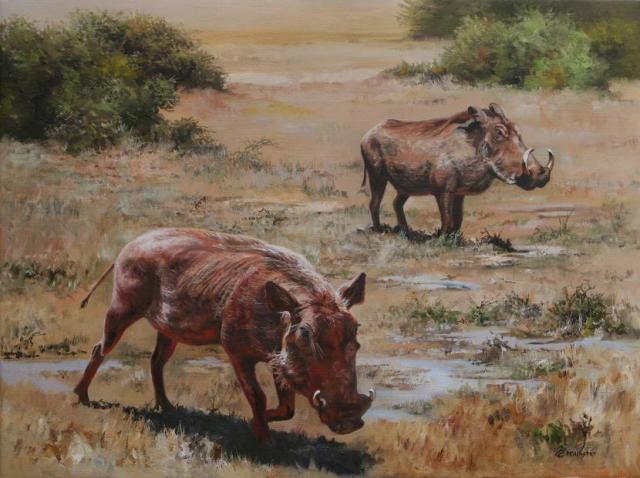

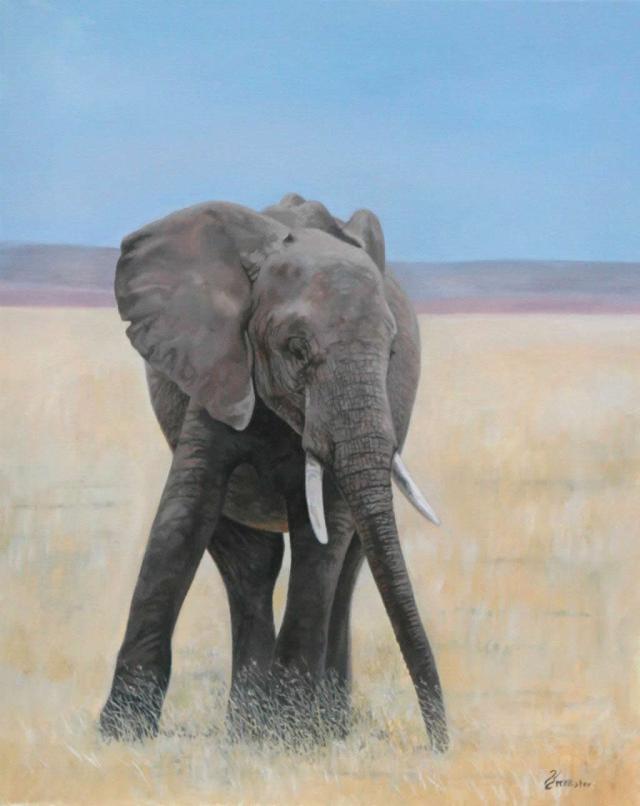

‘Curiosity’ Original Oil Painting by Keith McAllister